THE PORCELAIN ROSE

Paula Sengupta

September 24 – October 24, 2021

The porcelain rose or Etlingera elatior, a succulent plant indigenous to regions with tropical climate, encapsulates the essence of Paula Sengupta’s project. A native of the Southeast Asian humid rainforests, it is also found in the equatorial regions of Africa. The genus is named after eighteenth-century German botanist Andreas Ernst Etlinger, reflecting a well-established strategy of colonial nomenclature. The interregional associations of the plant are further enhanced by the evocation of porcelain—specialized pottery integral to Chinese art history.

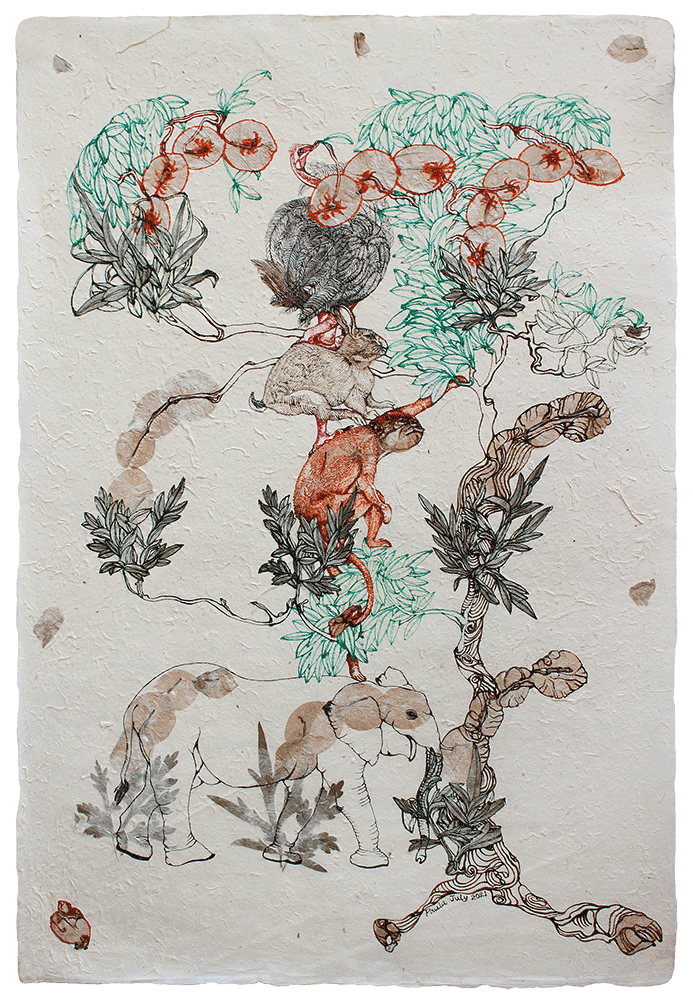

An avid artist, archivist and ethnographer, Sengupta arrives at this juncture through her persistent efforts to reclaim chintz—the masterfully dyed, painted and printed cotton of Coromandel, celebrated for its hybrid and transgressive visuals. In the historical chintz textile, rich intercultural socio-religious themes such as Kalpavriksha or the wish-fulfilling tree emerge as a repository of ambiguity — the meticulously drawn vegetal forms gradually evolving into elegant birds or ferocious predators.

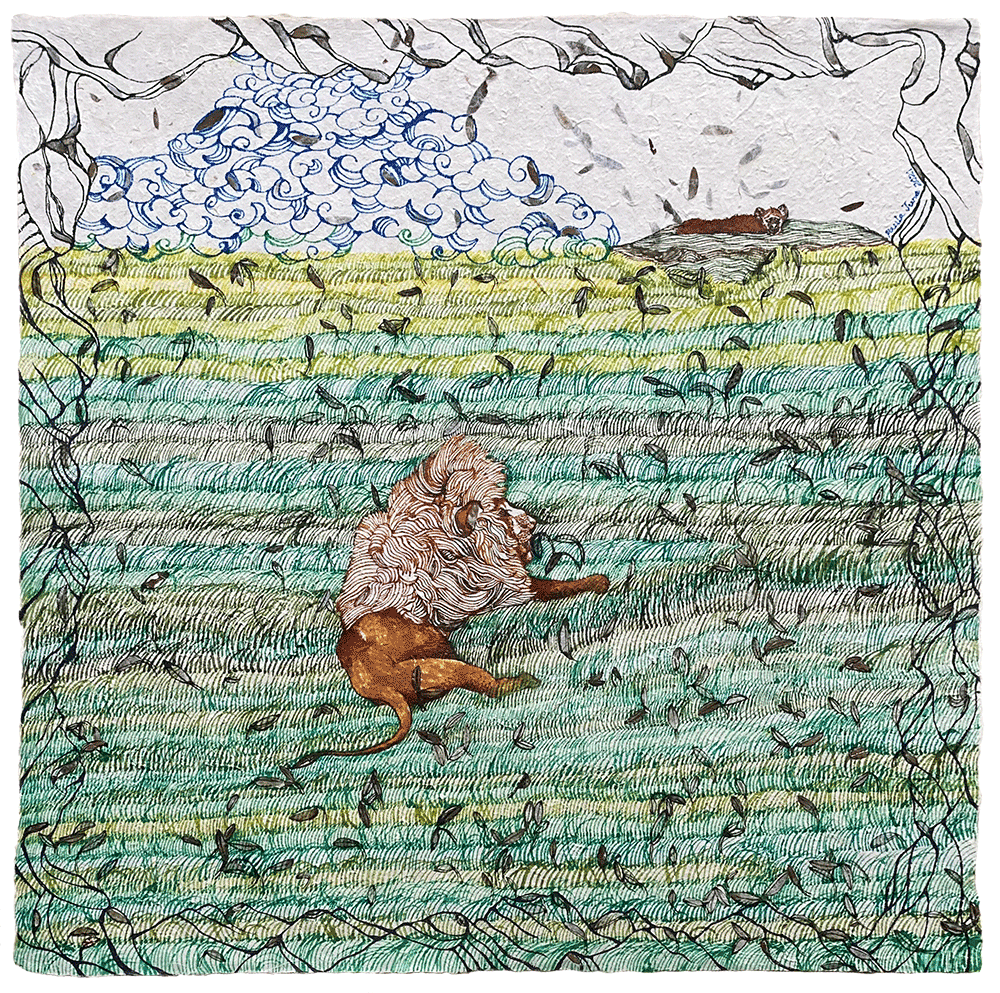

Camouflage or the act of concealment emerges in her recent works on display as a visual strategy to destabilize the frail boundary between serenity and uncertainty; it is also a reminder of the human condition, and of human folly in the guise of refinement.

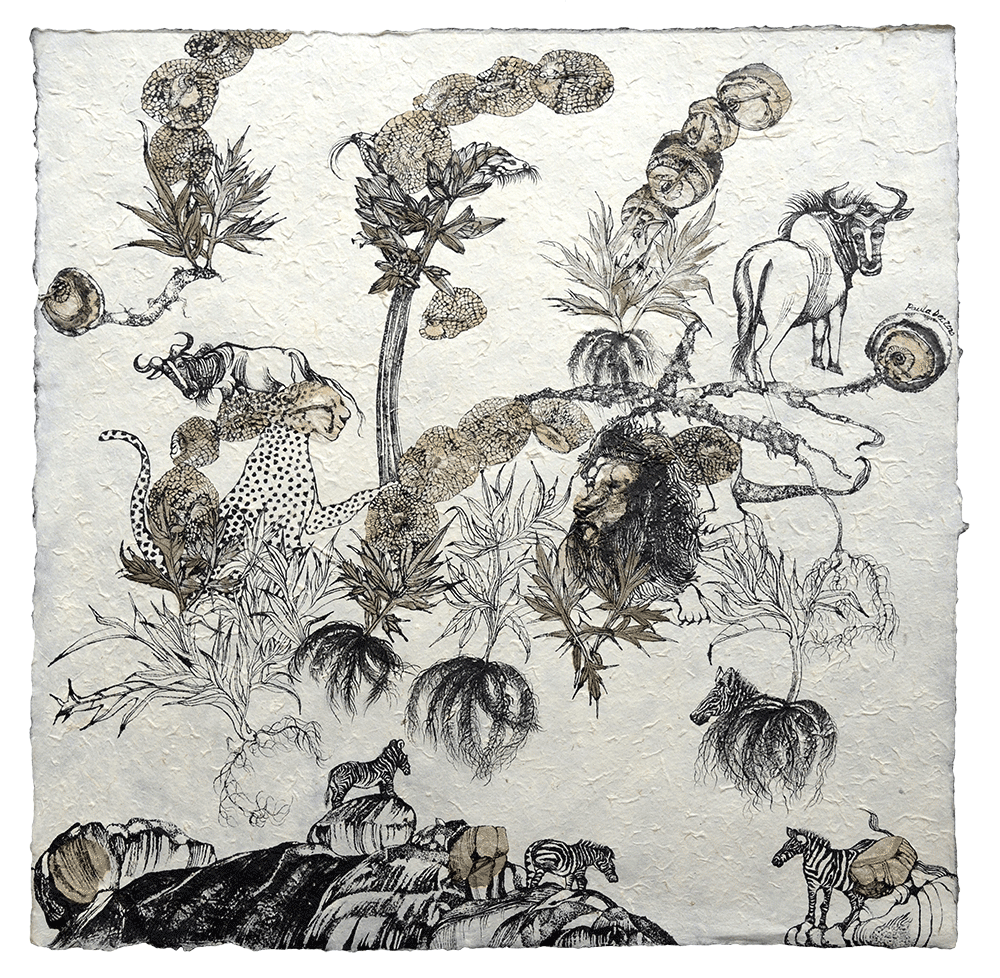

The sophisticated delineation of flora and fauna in her most recent drawings, wittily posed against paper with pressed plant specimens, compels us to see the tension between found and constructed visuals, and seemingly conclusive and preposterous narratives.

The Forest of Folly elucidates how the process of making the visuals aids the conceptual rigour. Upon settling their gaze on the picture, viewers are confronted with a majestic tiger with two tails lurking in a forest of flora-embedded rice paper. The pressed herbarium functions as the tangible residue of plants sheltering the predator as well as the wandering zebras and wildebeest. At places, the ink lines intersect with the plant specimens, pushing them to the background; in other instances, the pressed leaves are connected with brush lines to constitute branches of trees, denying a division between the figure and the ground.

About the artist

Dr. Paula Sengupta is an artist, academic, curator, and art writer. She is Professor at the Department of Graphics-Printmaking at the Faculty of Visual Arts, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

Trained as a printmaker, Paula’s repertoire as an artist includes broadsheets, artist’s books, objects, installation, and community art projects. She works across mediums that include printmaking, textiles and embroidery, papermaking, and much else. She is widely exhibited in India and abroad.

She is author of The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Printmaking published by the Delhi Art Gallery, New Delhi in 2012 and Foreign & Indigenous Influences in Indian Printmaking published by LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrucken, Germany in 2013.

“The word “Serengeti” means ‘endless plain’ in Masai. And it is truly endless. As far as the eye can see, it is a vast, limitless grassland, extending into the horizon and beyond. These are the Savannahs that I have read about since childhood, but witnessed for the first time here. I was told that in the summer, the grass dies out and this is a brown wasteland in which predators wander at large. Now, with afternoon thunderstorms washing the plain, we saw lions nestling and strolling through the grass at sundown, while leopards lounged camouflaged in tree branches in the afternoon sun.

– Paula Sengupta